Parallel Congress: A Concept Piece

Why We Need a Second Operating Layer for Democracy

By Ariel Willingham

I’ve spent most of my adult life managing systems—buildings, teams, schedules, operations. I learned early that when things fall apart, it’s rarely because people don’t care. It’s usually because the system can’t hear what’s happening inside it, can’t remember its own decisions, or can’t change course without breaking.

I don’t manage buildings anymore. I work on cultural repair.

This piece treats Congress the same way I’d treat any failing operation. Instead of arguing about ideology, it asks what structural changes would make the system easier to run, easier to correct, and harder to break. Parallel Congress is a thought experiment grounded in that question.

Successes in Systems

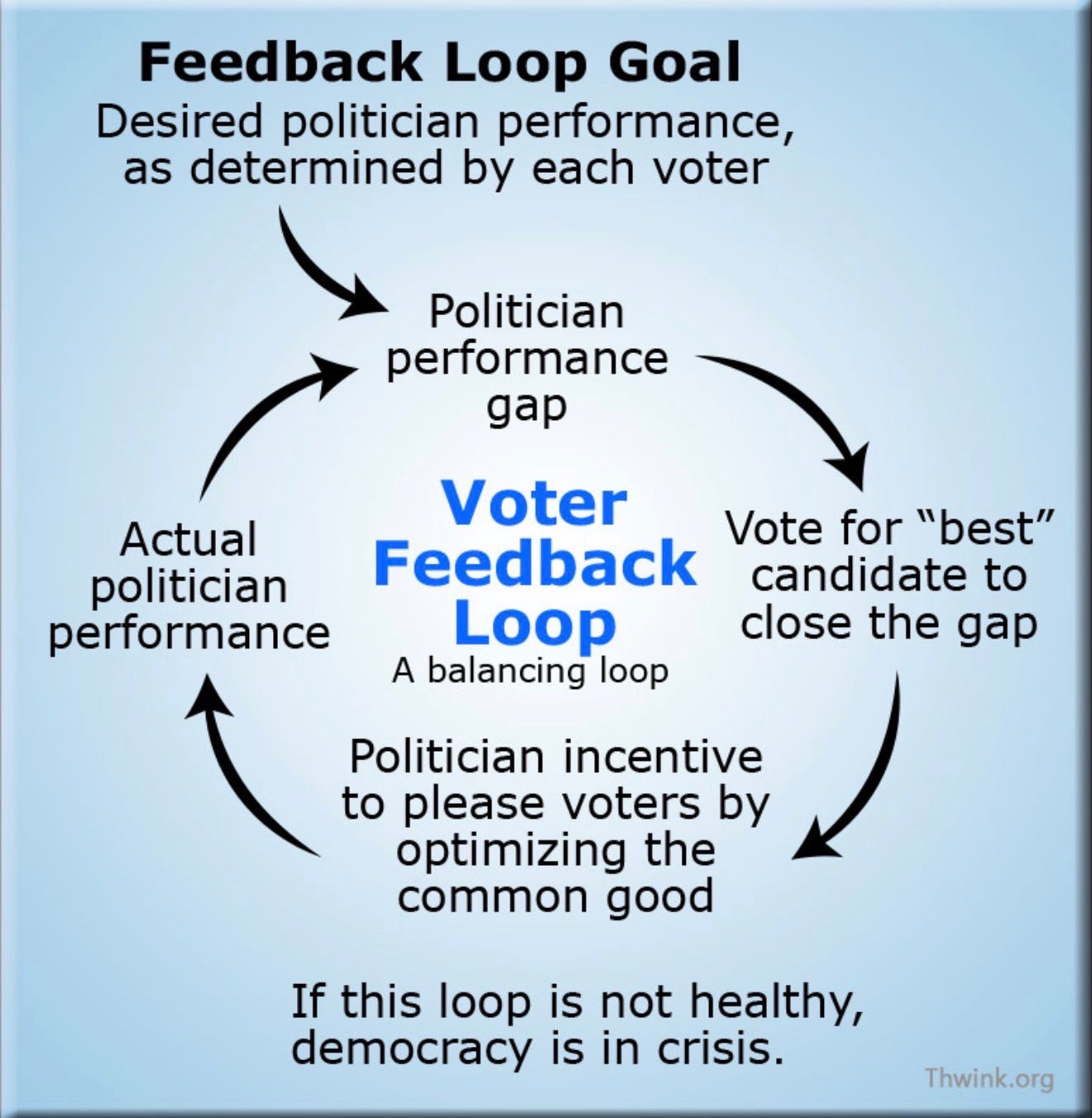

Every system that survives has three basic capacities:

1. It can sense what’s happening inside it

2. It shares information instead of hiding it

3. It can change course once harm is visible

Our government currently does none of these well. That’s not because people are stupid. It’s because the system itself is missing critical organs.

Congress does not reliably hear lived experience. It does not share decisions in a way people can understand. And once a policy causes harm, there is no clean, trusted mechanism to revise it.

So what fills the gap?

• Media outrage

• Court cases

• Leaks

• Protests

• Elections that ask voters to adjudicate years of accumulated damage in a single moment

I’m not defining this as democracy. This is system failure management.

The Real Questions

We keep arguing about politics as if disagreement is the problem. Left versus right. Red versus blue. More government versus less government. But none of those debates touch the actual failure.

The real questions are structural— and until we ask them, nothing changes.

Can the system tell what is actually happening?

Not in theory. Not through polling. Not through press conferences.

In practice.

Can it detect:

• when a policy is quietly hurting people before it becomes a scandal?

• when a regulation works on paper but fails in real life?

• when incentives are being gamed while outcomes look “successful”?

Right now, Congress learns reality the same way the public does: through crisis, outrage, or litigation—after the damage is done.

That is not governance. That is post-hoc damage control.

Can decision-makers see consequences before they lock them in?

Most legislation is passed under conditions of:

• incomplete information

• time pressure

• partisan performance

• and lobbying distortion

Members of Congress are forced to predict the future without feedback loops. They vote first. Reality arrives later.

And when the outcome is harmful, there is no clean mechanism to say:

“We were wrong. Here’s what changed. Here’s the fix.”

Instead, we get denial, blame-shifting, or silence—because acknowledging failure carries political cost.

A system that punishes course correction will always choose stubbornness over truth.

Are incentives aligned with learning—or with survival?

This is the part we rarely say out loud. Congress is not incentivized to be right. It is incentivized to win, retain power, and avoid blame.

That means:

• short-term optics beat long-term outcomes

• symbolic bills beat functional ones

• crisis response beats prevention

• and ambiguity beats clarity

When political survival depends on appearing confident, the system cannot admit uncertainty. So it stops asking real questions.

Who pays the price when predictions fail?

Not the authors of the bill. Not the committees. Not the lobbyists.

The cost of bad predictions is externalized to:

• workers

• families

• local governments

• frontline institutions

Congress makes choices under uncertainty. The public absorbs the consequences. And because those consequences are diffuse, delayed, and fragmented, they rarely translate back into accountability.

This is why the same failures repeat.

Can the system revise decisions without humiliation or collapse?

In a healthy system, revision is a strength.

In our political system, revision is treated as:

• weakness

• flip-flopping

• betrayal

• incompetence

So policies persist long after evidence says they should change. Not because leaders don’t care— but because the system cannot metabolize being wrong. A structure that cannot revise itself will eventually break.

Is disagreement actually the problem—or is blindness?

We assume polarization is the core issue. But disagreement is normal in any complex society.

The real danger is this:

We are arguing inside a system that cannot see itself.

Without shared reality:

• debate becomes performance

• facts become weapons

• and trust erodes completely

You cannot deliberate your way out of a system that lacks feedback.

Why Congress Can’t Tell What’s Going to Happen

This isn’t a moral failure. It’s an architectural one.

Congress operates without:

• a real-time sensory system

• protected channels for lived experience

• shared, legible decision records

• or safe pathways to revise course

It is asked to govern a complex, fast-moving society using quarterly elections, lagging indicators, media narratives, and political intuition.

No airline would fly this way. No hospital would operate this way. No business would survive this way. And yet we expect government to.

What This Means

If Congress cannot sense harm early, understand consequences as they emerge, or adapt without political suicide… then no amount of good intention will save it.

This is why the answer isn’t better people, louder arguments or higher stakes elections.

The answer is new incentive-aligned infrastructure—a system that makes learning, correction, and transparency the safest option.

That’s why Parallel Congress is being proposed.

Not a critique. A support structure.

Parallel Congress Proposal

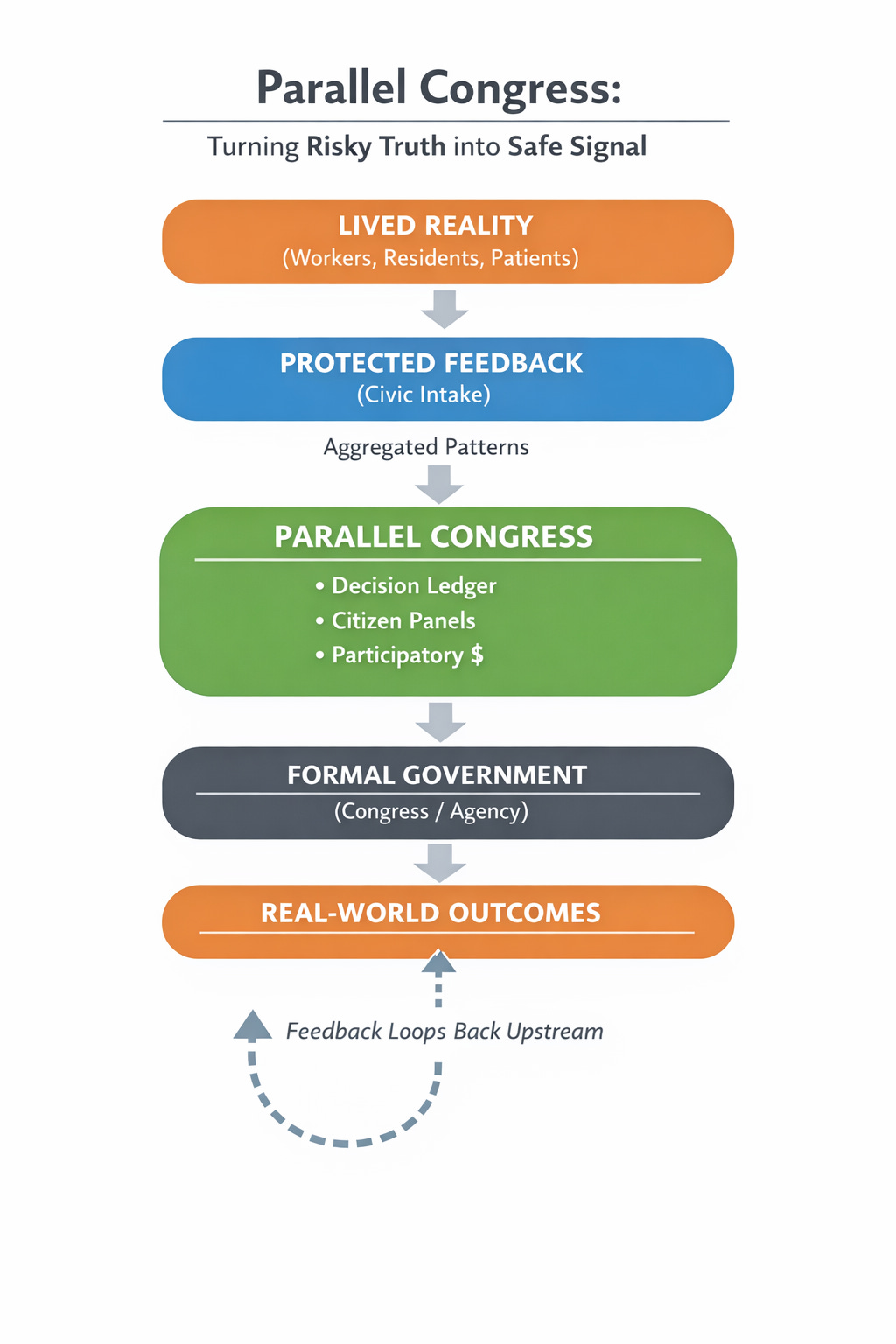

Parallel Congress would not a protest, a party, or a replacement government.

It is a second operating layer, designed to give democracy the capacities it currently lacks— without burning the house down.

It does not override Congress. It feeds Congress reality.

Think of it as adding a nervous system (feedback), a shared memory (commons), and reflexes (adaptive response) to a body that’s been running on crisis response alone.

How Parallel Congress Would Work

1. A Civic Sensory Layer (Feedback)

Parallel Congress begins with a protected intake system for lived experience:

- workers

- residents

- patients

- students

- frontline professionals

Reports are structured, anonymized when necessary, and aggregated into pattern-level signals.

This is not social media. Not complaints. Not anecdotes. The goal isn’t blame— it’s early detection.

Instead of learning after harm metastasizes, the system learns upstream.

2. A Public Decision Ledger (Commons)

Every major public decision processed through Parallel Congress receives a public-facing record:

• What was decided

• Who decided

• Why

• What evidence was used

• Who benefits

• How the decision can be challenged or revised

Written in plain language. This isn’t surveillance— It’s shared memory. When decisions are legible, trust doesn’t have to be demanded.

It can be earned.

3. A Deliberative Thinking Body (Adaptive Judgment)

Parallel Congress uses representative citizen panels:

• randomly selected

• demographically balanced

• given time, data, expert input, and lived-experience testimony

They don’t campaign. They don’t posture. They deliberate.This model already exists and is well documented by institutions like the OECD.

What Parallel Congress adds is non-negotiable:

Their conclusions must connect to real decision pathways— hearings, votes, rulemaking, budgets— or trigger a public explanation for non-adoption.

Nothing disappears into “consideration.”

4. A Real Lever: Participatory Budgeting

Parallel Congress includes a scoped portion of public funds allocated directly by residents:

• propose

• deliberate

• vote

• fund

• review outcomes

This restores something politics alone can’t:

Cause and effect.

When people can see “we chose this, and this happened,” trust stops being abstract.

Why This Changes Incentives

Right now, the political system rewards the wrong behaviors.

Members of Congress are incentivized to appear confident even when information is incomplete, avoid admitting uncertainty or error, defend past decisions regardless of new evidence, or delay acknowledgment of harm until it becomes unavoidable.

This is not because individual legislators lack integrity.

It’s because the cost of being wrong is personal and immediate, while the cost of being right is delayed and diffuse.

Parallel Congress changes this by shifting where risk lives.

By creating protected feedback channels, shared decision records, and legitimized deliberative outputs, the system stops treating new information as a threat and starts treating it as input.

When lived experience is aggregated and surfaced as patterns—not accusations—no single actor has to “take the fall” for reality asserting itself.

When decisions come with public receipts, the focus shifts from who to blame to what to adjust.

And when citizen deliberation is institutionalized, course correction becomes a collective act, not a political confession.

In short:

Parallel Congress makes learning safer than denial.

Not by appealing to virtue—

but by redesigning the incentive environment so that adaptation carries less risk than pretending nothing is wrong.

Why This Is the Smallest Possible Fix

Parallel Congress does not attempt to solve politics.

It solves missing infrastructure.

Most proposed reforms fail because they aim too high:

- rewriting constitutions

- reshaping party systems

- fixing polarization or changing human nature

Parallel Congress does none of that. It adds only what the current system structurally lacks:

• a reliable way to sense lived reality

• a shared memory for public decisions

• and a legitimate pathway for revision once outcomes diverge from intent

Everything else already exists. Elections remain. Legislatures remain. Courts remain. Agencies remain.

Parallel Congress does not replace these institutions—it feeds them better information.

This is why it is the smallest viable intervention:

It does not require ideological agreement

It does not demand trust in advance

It does not depend on exceptional leaders

It simply acknowledges a basic systems truth:

Any complex system that cannot sense, remember, and adapt will eventually fail—no matter how well intentioned its designers were.

Parallel Congress restores those three capacities. Not as a revolution.

As maintenance.

If This Was Implemented

If a democracy needed a second operating layer—one that could hear reality, remember its decisions, and change course without collapsing—how would it be built?

If this worked, we wouldn’t start in Washington.

We’d start in the places where policies meet bodies:

classrooms, clinics, job sites, neighborhoods, offices with broken systems and tired people.

If this worked, the first thing we’d build is a way for people to tell the truth without paying for it.

Stories would gather. Signals would repeat. Shapes would emerge. The system wouldn’t ask who is at fault. It would ask what keeps happening.

That’s the moment truth becomes usable.

If this worked, no single story would be decisive.

Once reality could be heard, we’d make sure it wasn’t forgotten.

If this worked, decisions wouldn’t vanish into process or fog. They’d leave a trace, a simple public record: what was chosen, why, by whom, and on what basis. For public memory, and radical transparency.

If this worked, we’d gather people not because they’re loud or powerful, but because they’re representative. Only after listening and remembering would we invite judgment.

If this worked, we wouldn’t promise control.

We’d offer something smaller, and therefore real:

a place where choice meets outcome. It would finish building the parts we forgot to name.

Design Concepts

If Parallel Congress worked, it wouldn’t work because people suddenly agreed. It would work because it was designed to survive disagreement, fatigue, and human limits.

These are the concepts that would have to be true.

1. Design For Reality, Not Ideals

This system would not assume people are well-informed, calm, or paying close attention. It would assume the opposite: that people are busy, overwhelmed, and often reacting late. It wouldn’t rely on everyone doing the “right” thing. It would work even when attention drops, leadership changes, or enthusiasm fades. If a system only works when people are at their best, it won’t last. This one would be built for normal days.

2. Signal Over Noise

Parallel Congress wouldn’t try to capture every opinion or emotion. It wouldn’t chase the loudest voices or the most dramatic moments. Instead, it would look for repetition — the same issue showing up again and again, across different people and places. One story can move us, but patterns tell us where systems are breaking. The goal isn’t to amplify noise, but to notice when something won’t stop happening.

3. Aggregation Without Erasure

When information is combined, it often smooths away the people who are most affected. This system would be designed not to do that. It would pay attention to who is being impacted repeatedly, even if the numbers are small. It would treat gaps in data as meaningful, not as nothing. Combining information wouldn’t mean flattening it — it would mean seeing shape, not just averages.

4. Legibility as a First Principle

If Parallel Congress worked, people wouldn’t need special training to understand important decisions. You wouldn’t have to be an expert, a lawyer, or an insider to follow what happened and why. Decisions would be written in plain language, with tradeoffs explained clearly. This isn’t about oversimplifying. It’s about respecting people enough to explain what’s being done in their name.

5. Revision Without Humiliation

Most systems treat being wrong as a personal failure. That makes people defensive and slow to change. Parallel Congress would be built on the assumption that revision is normal. Policies would be expected to change as new information arrives. Admitting a mistake wouldn’t be a scandal — it would be part of how the system functions. When correction is safe, learning becomes possible.

6. Distributed Responsibility

No single person would be responsible for “telling the truth” or carrying the consequences alone. Feedback would come from many people. Deliberation would be shared. Decisions would belong to a process, not a hero or a villain. This matters because when responsibility is shared, people are more honest. Fear decreases, and reality has a better chance of getting through.

7. Small Levers, Real Consequences

Parallel Congress wouldn’t try to change everything at once. It would focus on specific questions, limited budgets, and concrete decisions. People would be able to see what was chosen and what happened next. Trust doesn’t come from big promises — it comes from watching cause and effect play out in real life. Small, visible changes do more than sweeping declarations.

8. Non-Response as a Signal

Right now, institutions can ignore feedback without leaving a trace. In this system, silence would count as information. If a recommendation wasn’t acted on, that choice would be visible and explained. Not to shame anyone — but to make avoidance legible. When non-response is recorded, it becomes part of the shared understanding instead of disappearing into frustration.

9. Parallel, Not Vertical

Parallel Congress would never sit above existing institutions. It wouldn’t replace Congress, agencies, or local governments. It would run alongside them, offering context, feedback, and collective judgment. Power would stay where it already is — but it would no longer operate in isolation. This makes the system harder to attack and easier to adopt.

10. Build Once, Learn Forever

Finally, Parallel Congress would never claim to be finished. It wouldn’t present itself as the answer. It would be designed to keep listening, adjusting, and evolving. The moment a system believes it has solved the problem for good, it starts drifting away from reality again. This one would stay unfinished on purpose.

Last Call, Cause I’m Mad Now

Not long ago, a manager said something to me that stayed with me. We were talking honestly about leadership, and we agreed that power over is easier. Fear works. Control works. People comply faster when they’re afraid. Then he paused and said, almost to himself, “You never give up on people.”

What he was noticing wasn’t kindness. It was a different operating assumption. I don’t lead by extracting behavior. I lead by designing conditions where people can recover, learn, and eventually take responsibility for the system with you. That approach is slower at first, and it feels riskier. But it creates something power over never does: trust, feedback, and long-term coherence.

That same question I asked him—what would it look like if they trusted you?—is the question behind this entire piece. Not just for managers, but for institutions. Not just for teams, but for democracy itself.

It is possible to be a good leader, do the right thing, and feel aligned while doing it. When leadership feels corrosive or dissonant, it’s often not because integrity is unrealistic— it’s because the system is built to reward control instead of learning. Parallel Congress is not about being nicer or more idealistic. It’s about building structures where trust is operationally rational, where feedback is safe, and where correction is normal.

I used to manage buildings. Now I facilitate cultural repair. The work is the same: you don’t give up on what’s inside the system. You fix what makes failure repeat. And you design in a way that lets people—and institutions—do the right thing without breaking themselves in the process.

Excellent article - thanks for writing it.